General intelligence, what is it?

The education system is built around siloed learning – you learn maths, you learn computer science, you learn chemistry. But most people that do well in maths and chemistry will find themselves at the top of their English class as well. And these people are almost certainly going to be referred to as ‘bright’ as they progress through life.

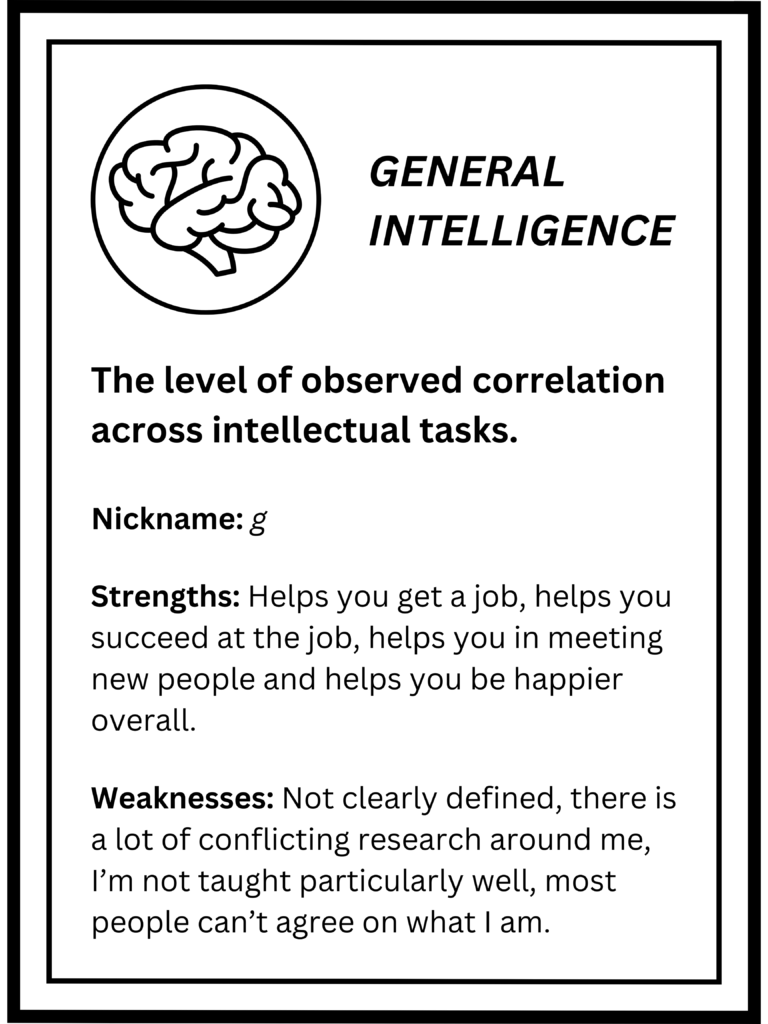

There all point to there being a general level of intelligence. What is general intelligence (or g – yes, general intelligence has its own letter) and why is it not taught at school and beyond?

Our old friend, g

If g were a sports player, what would its player card look like?

IQ is one way that psychologists have tried to quantify it, however this is a practical measure meant to estimate someone’s ability compared to a population. It does so via standardised tests. g goes a little deeper and is the representation of general cognitive ability underlying performance on cognitive tasks. It is derived from factor analyses of test scores, or sub-tests.

g will be measured from a variety of tests, but it won’t stem from the specific answers of the test – it will interpret the underlying results of the answers. Examples are how you reason in an arithmetic question, or what your verbal fluency is like when answering a question on the latest political drama. (Occasionally I’ll use IQ as a tool for g because although it’s not the same, it’s often the best measure available)

Psychologists and philosophers have had their theories on what general intelligence is. LL Thurstone identified seven primary mental abilities in 1938 that make up general intelligence, saying that each ability is completely separate and independent. These 7 abilities were verbal comprehension, word fluency, number facility, spatial visualisation, associative memory, perceptual speed and reasoning.

Taking a different view of it, John Carroll proposed a three stratum model in 1993 of intelligence consisting of three levels – with one ‘stratum’ focusing on broad factors that make up general intelligence. The 8 factors he described are fluid intelligence, crystallised intelligence, general memory and learning, broad visual perception, broad auditory perception, broad retrieval ability, broad cognitive speediness, and processing speed.

Some resources see it as important to only differentiate between crystallised intelligence (that which is learned like procedures and knowledge) and fluid intelligence (reasoning and mental activities that don’t depend on prior learning), or focus on the very broad categories of applying intelligence – that being analytical, practical and creative.

Although there is not one agreed upon structure of what makes up general intelligence, there is a common thread of what will make people come across as ‘bright.’

One interesting note in my research is that nothing I’ve come across mentions critical thinking as a trait of people with high general intelligence (my assumption is because it’s difficult to measure). I believe this is the single most important trait in intelligence though so should be factored in. However, because this article is mainly based on research to date, I won’t discuss in great depth. For an easy way to learn a lot about critical thinking and how to improve it (hint: like the below, it’s not easy), I recommend reading Excellent Sheep.

So what, why would g even matter?

Is there a correlation between general intelligence and success more broadly? Obviously defining what ‘success’ is needs its own article / novel, so let’s talk about whether there is correlation between general intelligence and two things:

- Doing well at school; and

- Success at your job.

Spoiler alert: the short answer to both is yes.

There is proof in research that not only does general mental ability correlate to success in one’s career, but that it “does so better than any other ability, trait, or disposition and better than job experience.” Intuitively this makes sense. The knowledge you get from experience when you have a high g is exponentially higher than if you have a low g. If you take in twice as much as someone else, then theoretically if you’re in the same job, you’ll learn twice as much from your experience – or do so in half them time.

A further study in 2013 found that g (or IQ) is “the single most important predictor of work success.” And a year earlier, Vanderbilt University psychology researchers found that people with higher IQs tend to earn higher incomes, on average, than those with lower IQs. There are a multitude of other studies showing high IQs are comparably reliable in predicting academic success, job performance, career potential and creativity.

It’s true that there are many other factors that go into being successful, and if you’re the smartest person in the world, you won’t necessarily be the most successful. However, there is sufficient evidence to say that increasing your general intelligence will increase your chances of success. This is particularly true in more complicated, skilled occupations. The type of occupations that are becoming more and more prevalent in today’s society.

Is it set or can it be improved as you get older?

General intelligence, if we look at the Thurstone model, is roughly taught to children at a young age (for example verbal comprehension and word fluency). It’s often taught until a sufficient level is reached that allows the student to transition to more siloed subjects (sometimes known as when the teacher is ready). Given the importance of reasoning, verbal comprehension, perceptual speed and so on to your career throughout your life, it seems these would be valuable to continue improving. Perhaps it’s because it can’t be improved?

A study in 1992 went a long way to disproving this theory though. The study was focused around people learning Tetris (remember in 1992 there were people then that didn’t know what Tetris was – or computers for that matter). The study was done by a neuroscientist who showed imagery of the the mental strain that people underwent to learn Tetris. During the early weeks, people had a significant increase in cortical thickness in the brain even when they weren’t playing – meaning more neural connections during the time of playing, and after. This is when a person’s intelligence is increasing. So this brain activity showed that it was possible to become smarter based on ‘working out’ (this was actually a novel concept in 1992).

So yes, brain training was possible, but did it transfer across topics and subjects – that was not known. It was not until 2008 when a very important paper came out proving that it is possible to train g. This study trained its participants on the game Dual-N-Back (a mighty tough game if you haven’t tried it – a good test of fluid intelligence), and it showed that people’s performance at the game improved quickly. This is expected, and to be honest, not very interesting at this point.

What was groundbreaking and fascinating about the study though was that the researchers tracked completely unrelated cognitive tasks, as well game performance. A group training on Dual-N-Back performed significantly better than a control group on these unrelated tasks – proving that intelligence (fluid intelligence specifically in this case) can be trained.

The study also highlighted two other very important findings:

- The training effect is not limited – the more you train, the more you gain.

- Anyone can improve their cognitive ability, regardless of starting point.

So this was all very promising, but it did note that these increases in fluid intelligence had a short half-life, i.e. the gains quickly evaporated.

Well then how can it be improved?

If you want to improve your intellect, it’s going to be hard work – which makes logical sense. If you decide you want to run a marathon, you’re not expecting to just jog outside for an hour a week – you’re committing to a significant (hard) change in your life that will take hours and hours of running a week.

Today, there are various options for improving your intelligence. One is going through the education system. The education system has many flaws [LINK], but it is siloed learning on specific topics and it is built around rote memory (cramming for end of year exams). Tests of rote memory have been shown to have the same level of difficulty but considerably lower g loadings than tests that involve reasoning.

Another option is to pick from the plethora of apps that promise to “5x your memory capacity” in “just 15 min / week” or make me smarter “with breeze and joy.” As we’ve learned though, there is no magic solution to improving your general intelligence – remember, it’s marathon training for the mind. Even when there are apps that exist that are proven to improve your intelligence (Dual-N-Back comes in app form), the Tetris study I mentioned earlier showed that once you got used to the game, your brain became so efficient that it did not require any brain loading at all (the brain is inherently lazy). This is to say you need to be constantly challenged to improve your intelligence.

The final option is the personal trainer method. This would involve hiring a tutor that teaches you from a general intelligence course every day (which may or may not exist). They would need a set curriculum of challenging classes that increases in difficulty gradually over time. They’d also need to keep the course content fresh given the brain’s propensity to get lazy. Given the difficulty of creating these types of learning experiences (dual-n-back is one of a kind), this will once again be a challenge.

One of the most misunderstood aspects to improving general intelligence is one of the most obvious when you read it, you need to work hard and think hard. If you do this with new and challenging curriculum frequently, you can improve your intelligence significantly.

Why is this interesting?

At an individual level – improving g improves your job prospects, your ability to perform well at your job (and school), allows you to contribute more to society and allows you to interact at a deeper level with more people. These are all tied to increasing happiness (noting there is not a direct correlation here).

On a societal level, the benefits may be even more pronounced. There are infinite problems that require solving in the world. There are ways to solve these with increased understanding. Raising the general intelligence level will mean more intelligence is deployed on solving these problems. Imagine we had the intelligence around to develop actual room temperature superconductors that worked (this was a buzz a few months back when it looked to be true, but was proven false). The benefits would be life-changing.

And looking at trends in the world, it’s clear that general intelligence is becoming more important. People are likely to change careers multiple times and technologies are being updated every year, forcing people to learn things on the fly. Furthermore, companies are taking on more of the burden of training staff at all levels. It’s obvious that general and fluid intelligence are the most sought after skills these days, yet they’re not taught anywhere.

Case study

Solving the entire problem discussed above is a monumental undertaking, but perhaps there are underrated skills that make up g that we can work on improving – at a level above primary school.

Take reading for example. I believe that there are adults that do it much better than other adults. Not only do some read faster, but some will take more in, some will remember more and some will apply more of what they read in the real world. I also believe that it’s one of the highest leverage skills you can improve.

- There are millions of free books at libraries (and very cheap at stores) for your access.

- Books have distilled the thoughts of the most successful people in the world and stored them for your access.

- All you need is eyesight (and maybe a notebook to take notes) to start learning.

- They can take from novice to expert on a topic with the right reading.

Previously, I’ve built an app to help people discover more great books in the world by sharing what they read with their friends.

Now, I’m interested in building the second part to the reading chain – helping people comprehend more from their reading. Believing that a little thought before you read, and some thoughts after you read, can drastically improve your comprehension, I’ve built an app to help you along this journey.

If this sounds like something you’re interested in, please reach out. It’s a rough prototype and very much in beta, but I’m keen to understand whether we can get more out of our reading.